History of Wales

| History of Wales |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

| People |

| Art |

The history of what is now Wales (Welsh: Cymru) begins with evidence of a Neanderthal presence from at least 230,000 years ago, while Homo sapiens arrived by about 31,000 BC. However, continuous habitation by modern humans dates from the period after the end of the last ice age around 9000 BC, and Wales has many remains from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age. During the Iron Age, as in all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth, the culture had become Celtic, with a common Brittonic language. The Romans, who began their conquest of Britain in AD 43, first campaigned in what is now northeast Wales in 48 against the Deceangli, and gained total control of the region with their defeat of the Ordovices in 79. The Romans departed from Britain in the 5th century, opening the door for the Anglo-Saxon settlement. Thereafter, the culture began to splinter into a number of kingdoms. The Welsh people formed with English encroachment that effectively separated them from the other surviving Brittonic-speaking peoples in the early middle ages.

In the post-Roman period, a number of Welsh kingdoms formed in present-day Wales, including Gwynedd, Powys, Ceredigion, Dyfed, Brycheiniog, Ergyng, Morgannwg, and Gwent. While some rulers extended their control over other Welsh territories and into western England, none were able to unite Wales for long. Internecine struggles and external pressure from the English, and later the Norman conquerors of England, led to the Welsh kingdoms coming gradually under the sway of the English crown. In 1282, the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd led to the conquest of the Principality of Wales by King Edward I of England; since then, the heir apparent to the English monarch has borne the title "Prince of Wales". The Welsh launched several revolts against English rule, the last significant one being that led by Owain Glyndŵr in the early 15th century. In the 16th century Henry VIII, himself of Welsh extraction as a great-grandson of Owen Tudor, passed the Laws in Wales Acts aiming to fully incorporate Wales into the Kingdom of England.

Wales became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 and then the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. Yet, the Welsh retained their language and culture despite heavy English dominance. The publication of the extremely significant first complete Welsh translation of the Bible by William Morgan in 1588 greatly advanced the position of Welsh as a literary language. The 18th century saw the beginnings of two changes that would greatly affect Wales: the Welsh Methodist revival, which led the country to turn increasingly nonconformist in religion, and the Industrial Revolution. During the rise of the British Empire, 19th century Southeast Wales in particular experienced rapid industrialisation and a dramatic rise in population as a result of the explosion of the coal and iron industries. Wales played a full and willing role in World War One. The industries of the Empire in Wales declined in the 20th century with the end of the British Empire following the Second World War, while nationalist sentiment and interest in self-determination rose. The Labour Party replaced the Liberal Party as the dominant political force in the 1920s. Wales played a considerable role during World War Two, along with the rest of the United Kingdom and its allies, and its cities were bombed extensively during the Blitz. The nationalist party Plaid Cymru gained momentum from the 1960s. In a 1997 referendum, Welsh voters approved the devolution of governmental responsibility to a National Assembly for Wales which first met in 1999, and was renamed as the Senedd Cymru/Welsh Parliament in May 2020.

Prehistoric era

[edit]Paleolithic

[edit]The earliest known item of human remains discovered in modern-day Wales is a Neanderthal jawbone, found at the Bontnewydd Palaeolithic site in the valley of the River Elwy in North Wales; it dates from about 230,000 years before present (BP) in the Lower Palaeolithic period,[1] and from then, there have been skeletal remains found of the Paleolithic Age man in multiple regions of Wales, including South Pembrokeshire and Gower.[2] It is known that Britain was visited over a long period during interglacial periods, perhaps as far back as far as an interstadial period of the Mindel glaciation, some 300,000 years ago,[3] but in the last Glacial Maximum, 26,000-20,000 BP, most of Wales was covered in an ice sheet. Despite this, Wales has been inhabited by modern humans for at least 29,000 years.[4] The Red Lady of Paviland, a human skeleton dyed in red ochre, was discovered in 1823 in one of the Paviland limestone caves of the Gower Peninsula in Swansea, South Wales. Despite the name, the skeleton is that of a young man who lived about 33,000 BP at the end of the Upper Paleolithic Period (Old Stone Age). Paviland cave lay just to the south of the ice sheet and the sea level was lower, so the cave was inland at the time.[5] It is considered to be the oldest known ceremonial burial in Western Europe. The skeleton was found along with jewellery made from ivory and seashells and a mammoth's skull.

Mesolithic and Neolithic

[edit]Continuous human habitation dates from the end of the last ice age, between 12,000 and 10,000 years before present (BP), when Mesolithic (middle stone age) hunter-gatherers from Central Europe began to migrate to Great Britain. At that time, sea levels were much lower than today. Wales was free of glaciers by about 10,250 BP, the warmer climate allowing the area to become heavily wooded. The post-glacial rise in sea level separated Wales and Ireland, forming the Irish Sea. By 8,000 BP the British Peninsula had become an island.[6][7][8] Following the last ice age, Wales became roughly the shape it is today by about 8000 BC and was inhabited by small numbers (a few hundred) of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. These people lived in caves and wood-contructed houses, the latter of which have not stood the test of time.[9][10] The earliest farming communities are now believed to date from about 4000 BC, marking the beginning of the Neolithic period. This period saw the construction of many chambered tombs, particularly dolmens or cromlechs. The most notable examples of megalithic tombs include Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad y Gawres on Anglesey,[11] Pentre Ifan in Pembrokeshire, and Tinkinswood Burial Chamber in the Vale of Glamorgan.[12] By the beginning of the Neolithic (c. 6,000 BP) sea levels in the Bristol Channel were still about 33 feet (10 metres) lower than today.[13][14] The historian John Davies theorised that the story of Cantre'r Gwaelod's drowning and tales in the Mabinogion, of the waters between Wales and Ireland being narrower and shallower, may be distant folk memories of this time.[15]

Neolithic (new stone age) colonists integrated with the indigenous people, gradually changing their lifestyles from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering, to become settled farmers about 6,000 BP – the Neolithic Revolution.[15][16] They cleared the forests to establish pasture and to cultivate the land, developed new technologies such as ceramics and textile production, and built cromlechs such as Pentre Ifan, Bryn Celli Ddu, and Parc Cwm long cairn between about 5,800 BP and 5,500 BP.[17][18]

Bronze Age

[edit]

Metal tools first appeared in Wales about 2500 BC, initially copper followed by bronze. The climate during the Early Bronze Age (c. 5000–1400 BC) is thought to have been warmer than at present, as there are many remains from this period in what are now bleak uplands. The Late Bronze Age (c. 1400–750 BC) saw the development of more advanced bronze implements. Much of the copper for the production of bronze probably came from the copper mine on the Great Orme, where prehistoric mining on a very large scale dates largely from the middle Bronze Age.[19] Radiocarbon dating has shown the earliest hillforts in what would become Wales to have been constructed during this period. Historian John Davies theorises that a worsening climate after around 1250 BC (lower temperatures and heavier rainfall) required more productive land to be defended.[20]

Over the centuries following their initial settlement, the Neolithic population assimilated immigrants and adopted ideas from Bronze Age and Iron Age Celtic cultures. Some historians, such as John T. Koch, consider Wales in the Late Bronze Age as part of a maritime trading-networked culture that included other Celtic nations.[21][22][23] This "Atlantic-Celtic" view is opposed by others who hold that the Celtic languages derive their origins from the more easterly Hallstatt culture.[24]

Iron Age

[edit]The earliest iron implement found in Wales is a sword from Llyn Fawr which overlooks the head of the Vale of Neath, which is thought to date to about 600 BC.[25] Hillforts continued to be built during the British Iron Age. Nearly 600 hillforts are in Wales, over 20% of those found in Britain, examples being Pen Dinas near Aberystwyth and Tre'r Ceiri on the Llŷn peninsula.[20] A particularly significant find from this period was made in 1943 at Llyn Cerrig Bach on Anglesey when the ground was being prepared for the construction of a Royal Air Force base. The cache included weapons, shields, chariots along with their fittings and harnesses, and slave chains and tools. Many had been deliberately broken and seem to have been votive offerings.[26]

A tendency to see the creation of hillforts as evidence of a Celtic invasion that also brought a Celtic language to the Britain has been dealt a blow by recognition that the earliest forts predate the arrival of Iron Age Celtic culture by hundreds of years. The present tendency is to reject the hypothesis of mass invasion in favour of more sporadic migration and a cultural spread of language and ideas, a "culminative Celticity".[20] Then, with the coming of the Celts, there was an agricultural improvement of farming in Britain. This is evident with the then new use of the iron ploughshare, a type of Plough.[27]

Iron Age Celts

[edit]During the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age in Celtic Britain (c. 800 BC) is when modern-day Wales was split into 4 regional tribes. They were, the Ordovices (Mid Wales to North West Wales), the Deceangli (North East Wales, North Wales), the Silures (South East Wales, Mid Wales) and the Demetae (South West Wales).[28] A second wave (c. 500 BC- 200 BC) of migration of Celtic tribes from Eastern Europe emerged in Britain and established stone hut circle roundhouse settlements within or near the previously inhabited hillfort enclosures. Hut circles were used as dwellings until after the end of Roman rule in Britain. During the Roman occupation, another Celtic Briton tribe in modern-day Wales was identified as the Gangani (Llŷn Peninsula, North West Wales), they were a tribe with connections to Ireland.[29]

Roman era

[edit]

The Roman conquest of Wales began in AD 48 and took 30 years to complete; the occupation lasted over 300 years.[30] The most famous resistance was led by Caratacus of the Catuvellauni tribe (modern day Essex), who were defeated by the Romans. Caratacus then fled to the Silures (of present day Monmouthshire) and the Ordovices (of North Wales) and led them in a war against the Romans. His forces were eventually defeated and Caratacus was handed over to the Romans. He was taken to Rome and gave a speech, impressing the Roman emperor to the extent that he was pardoned and allowed to live peacefully in Rome.[31]

The Roman conquest was completed in 78, with Roman rule lasting until 383. Roman rule in Wales was a military occupation, save for the southern coastal region of South Wales east of the Gower Peninsula, where there is a legacy of Romanisation.[30] The only town in Wales founded by the Romans, Caerwent, is located in South Wales. Both Caerwent and Carmarthen, also in southern Wales, would become Roman civitates.[32]

By AD 47, Rome had invaded and conquered all of southernmost and southeastern Britain under the first Roman governor of Britain. As part of the Roman conquest of Britain, a series of campaigns to conquer Wales was launched by his successor in 48 and would continue intermittently under successive governors until the conquest was completed in 78. It is these campaigns of conquest that are the most widely known feature of Wales during the Roman era due to the spirited but unsuccessful defence of their homelands by two native tribes, the Silures and the Ordovices.

The Demetae of southwestern Wales seem to have quickly made their peace with the Romans, as there is no indication of war with Rome, and their homeland was not heavily planted with forts nor overlaid with roads. The Demetae would be the only Welsh tribe to emerge from Roman rule with their homeland and tribal name intact.[a]

Wales was a rich source of mineral wealth, and the Romans used their engineering technology to extract large amounts of gold, copper, and lead, as well as modest amounts of some other metals such as zinc and silver.[34] When the mines were no longer practical or profitable, they were abandoned. Roman economic development was concentrated in southeastern Britain, with no significant industries located in Wales.[34] This was largely a matter of circumstance, as Wales had none of the needed materials in suitable combination, and the forested, mountainous countryside was not amenable to development. Latin became the official language of Wales, though the people continued to speak in Brythonic. While Romanisation was far from complete, the upper classes came to consider themselves Roman, particularly after the ruling of 212 that granted Roman citizenship to all free men throughout the Empire.[35] Further Roman influence came through the spread of Christianity, which gained many followers when Christians were allowed to worship freely; state persecution ceased in the 4th century, as a result of Constantine the Great issuing an edict of toleration in 313.[35]

Early historians, including the 6th-century cleric Gildas, have noted 383 as a significant point in Welsh history.[36] In that year, the Roman general Magnus Maximus stripped Britain of troops to launch a successful bid for imperial power, continuing to rule Britain from Gaul as emperor from 383 to 388, and transferring power to local leaders.[37][38] Subsequent medieval Welsh lore developed a series of legends around Macsen Wledig, a literary and mythical figure derived from Magnus Maximus.[39][40] Several medieval Welsh dynasties claimed that they were descended from Macsen, thereby linking their origins to the legitimacy and prestige of a Roman past.[39][40] Thus, the earliest Welsh genealogies cite Maximus as the founder of several royal dynasties,[41][42] and as the father of the Welsh nation.[36] He is given as the ancestor of a Welsh king on the Pillar of Eliseg in the 9th century,[43] erected nearly 500 years after he left Britain, and he appears in lists of the Fifteen Tribes of Wales.[44] Later Welsh genealogies, medieval poetry, for example the Mabinogion, and chronicles such as the Historia Brittonum and Annales Cambriae, used myths and legends to give roles in Welsh history to historical and quasi-historical figures from the Roman and Sub-Roman periods. Aside from Macsen Wledig, other such figures include St Helena, the Emperor Constantine and Coel Hen.[45]

Early Middle Ages: 383–1066

[edit]The 400-year period following the collapse of Roman rule is the most difficult to interpret in the history of Wales.[35] When the Roman garrison of Britain was withdrawn in 410, the various British states were left self-governing. Evidence for a continuing Roman influence after the departure of the Roman legions is provided by an inscribed stone from Gwynedd dated between the late 5th and mid-6th centuries commemorating a certain Cantiorix who was described as a citizen (cives) of Gwynedd and a cousin of Maglos the magistrate (magistratus).[46] There was considerable Irish colonisation in Dyfed, where there are many stones with ogham inscriptions.[47] Wales had become Christian under the Romans, and the Age of the Saints (approximately 500–700) was marked by the establishment of monastic settlements throughout the country, by religious leaders such as Saint David, Illtud and Saint Teilo.[48]

One of the reasons for the Roman withdrawal was the pressure put upon the empire's military resources by the incursion of barbarian tribes from the east. These tribes, including the Angles and Saxons, gradually took control of eastern and southern Britain.[49] After the Roman departure in AD 410, much of the lowlands of Britain to the east and south-east was overrun by various Germanic peoples, commonly known as Anglo-Saxons. Some have theorized that the cultural dominance of the Anglo-Saxons was due to apartheid-like social conditions in which the Britons were at a disadvantage.[50]

By AD 500 the land that would become Wales had divided into a number of kingdoms free from Anglo-Saxon rule.[35] The kingdoms of Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed, Caredigion, Morgannwg, the Ystrad Tywi, and Gwent emerged as independent Welsh successor states.[35] The largest of these being Gwynedd in northwest Wales and Powys in the east. Gwynedd was the most powerful of these kingdoms in the 6th and 7th centuries, under rulers such as Maelgwn Gwynedd (died 547)[51] and Cadwallon ap Cadfan (died 634/5)[52] who in alliance with Penda of Mercia was able to lead his armies as far as the Kingdom of Northumbria and control it for a period. Following Cadwallon's death in battle the following year, his successor Cadafael Cadomedd ap Cynfeddw also allied himself with Penda against Northumbria but thereafter Gwynedd, like the other Welsh kingdoms, was mainly engaged in defensive warfare against the growing power of Mercia.

Archaeological evidence, in the Low Countries and what was to become England, shows early Anglo-Saxon migration to Great Britain reversed between 500 and 550, which concurs with Frankish chronicles.[53] John Davies notes this as consistent with a victory for the Celtic Britons at Badon Hill against the Saxons, which was attributed to Arthur by Nennius.[53]

At the Battle of Chester in 616, the forces of Powys and other British kingdoms were defeated by the Northumbrians under Æthelfrith, with king Selyf ap Cynan among the dead.[49] It has been suggested that this battle finally severed the land connection between Wales and the kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North"), the Brittonic-speaking regions of what is now southern Scotland and northern England, including Rheged, Strathclyde, Elmet and Gododdin, where Old Welsh was also spoken.[citation needed] From the 8th century on, Wales was by far the largest of the three remnant Brittonic areas in Britain, the other two being the Hen Ogledd and Cornwall.

Having lost much of what is now the West Midlands to Mercia in the 6th and early 7th centuries, a resurgent late-7th-century Powys checked Mercian advances. Æthelbald of Mercia, looking to defend recently acquired lands, had built Wat's Dyke. According to Davies, this had been with the agreement of king Elisedd ap Gwylog of Powys, as this boundary, extending north from the valley of the River Severn to the Dee estuary, gave him Oswestry.[54] Another theory, after carbon dating placed the dyke's existence 300 years earlier, is that it was built by the post-Roman rulers of Wroxeter.[55] King Offa of Mercia seems to have continued this initiative when he created a larger earthwork, now known as Offa's Dyke (Clawdd Offa). Davies wrote of Cyril Fox's study of Offa's Dyke: "In the planning of it, there was a degree of consultation with the kings of Powys and Gwent. On the Long Mountain near Trelystan, the dyke veers to the east, leaving the fertile slopes in the hands of the Welsh; near Rhiwabon, it was designed to ensure that Cadell ap Brochwel retained possession of the Fortress of Penygadden." And, for Gwent, Offa had the dyke built "on the eastern crest of the gorge, clearly with the intention of recognizing that the River Wye and its traffic belonged to the kingdom of Gwent."[54] However, Fox's interpretations of both the length and purpose of the Dyke have been questioned by more recent research.[56]

The southern and eastern parts of Great Britain lost to English settlement became known in Welsh as Lloegyr (Modern Welsh Lloegr), which may have referred to the kingdom of Mercia originally and which came to refer to England as a whole.[b] The Germanic tribes who now dominated these lands were invariably called Saeson, meaning "Saxons". The Anglo-Saxons called the Romano-British *Walha, meaning 'Romanised foreigner' or 'stranger'.[57] The Welsh continued to call themselves Brythoniaid (Brythons or Britons) well into the Middle Ages, though the first written evidence of the use of Cymru and y Cymry is found in a praise poem to Cadwallon ap Cadfan (Moliant Cadwallon, by Afan Ferddig) c. 633.[58] In Armes Prydein, believed to be written around 930–942, the words Cymry and Cymro are used as often as 15 times.[59] However, from the Anglo-Saxon settlement onwards, the people gradually begin to adopt the name Cymry over Brythoniad.[60]

From 800 onwards, a series of dynastic marriages led to Rhodri Mawr's (r. 844–77) inheritance of Gwynedd and Powys. His sons founded the three dynasties of Aberffraw for Gwynedd, Dinefwr for Deheubarth and Mathrafal for Powys. Rhodri's grandson Hywel Dda (r. 900–50) founded Deheubarth out of his maternal and paternal inheritances of Dyfed and Seisyllwg in 930, ousted the Aberffraw dynasty from Gwynedd and Powys and then codified Welsh law in the 940s.[61]

Rise and fall Gwynedd: 401–1283

[edit]

Eventually, after the 5th century, Wales was unified and ruled again by the Brythonic Celtic tribes who inhabited the lands. The Kingdom of Gwynedd was established in North West Wales during the year 401 by Cunedda Wledig, a Roman soldier who hailed from Manaw Gododdin (Scotland) to pacify the invading fellow Celts from Ireland.[62]

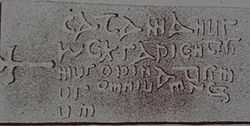

The rulers of Gwynedd would establish a Kingdom as descendants of the final Kings of Britain. During the age of Cadwaladr (last King of Britain, Prince of Gwynedd c. 660s), his family settled the lands of Southwest Anglesey as patrons of St Cadwaladr's Church, Llangadwaladr, an inscription in Latin is still found in the Church today speaks of his grandfather (Cadfan ap Iago), "the Wisest and Most Renowned of All Kings".[62][63][64]

By the 700s, Powys as the easternmost of the major kingdoms of Wales came under the most pressure from the English in Cheshire, Shropshire and Herefordshire. This kingdom originally extended east into areas now in England, and its ancient capital, Pengwern, has been variously identified as modern Shrewsbury or a site north of Baschurch.[65] These areas were lost to the kingdom of Mercia. The construction of the earthwork known as Offa's Dyke (usually attributed to Offa of Mercia in the 8th century) may have marked an agreed border.[66]

For a single man to rule the whole country during this period was rare. This is often ascribed to the inheritance system practised in Wales. All sons received an equal share of their father's property (including illegitimate sons), resulting in the division of territories. However, the Welsh laws prescribe this system of division for land in general, not for kingdoms, where there is provision for an edling (or heir) to the kingdom to be chosen, usually by the king. Any son, legitimate or illegitimate, could be chosen as edling and there were frequently disappointed candidates prepared to challenge the chosen heir.[c]

The King Rhodri Mawr later established a new dynasty (c. 870s AD) by constructing a royal palace at Aberffraw, it was named after the village it was located at, the House of Aberffraw on Anglesey, then in the Kingdom of Gwynedd.[68][69] Rhodri was able to extend his rule to Powys and Ceredigion.[70] On his death his realms were divided between his sons. Rhodri's grandson, Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), formed the kingdom of Deheubarth by joining smaller kingdoms in the southwest and had extended his rule to most of Wales by 942.[71] He is traditionally associated with the codification of Welsh law at a council which he called at Whitland, the laws from then on usually being called the "Laws of Hywel". Hywel followed a policy of peace with the English. On his death in 949 his sons were able to keep control of Deheubarth but lost Gwynedd to the traditional dynasty of this kingdom.[72]

Wales was now coming under increasing attack by Vikings, particularly Danish raids in the period between 950 and 1000. According to the chronicle Brut y Tywysogion, Godfrey Haroldson carried off two thousand captives from Anglesey in 987, and the king of Gwynedd, Maredudd ab Owain is reported to have redeemed many of his subjects from slavery by paying the Danes a large ransom.[73]

In 853, the Vikings raided Anglesey, but in 856, Rhodri Mawr defeated and killed their leader, Gorm.[74] The Celtic Britons of Wales made peace with the Vikings and Anarawd ap Rhodri allied with the Norsemen occupying Northumbria to conquer the north.[75] This alliance later broke down and Anarawd came to an agreement with Alfred, king of Wessex, with whom he fought against the west Welsh. According to Annales Cambriae, in 894, "Anarawd came with the Angles and laid waste to Ceredigion and Ystrad Tywi."[76]

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was the only ruler to be able to unite the Welsh kingdoms under his rule. Originally king of Gwynedd, by 1055 he was ruler of almost all of Wales and had annexed parts of England around the border. However, he was defeated by Harold Godwinson in 1063 and killed by his own men. His territories were again divided into the traditional kingdoms.[77][78] Llywelyn II (the last) became the first official Prince of Wales and inherited the lands gained by his father, Llywelyn the Great. He was appointed Prince by the English Crown in 1267. In 1282, he was ambushed and killed without a male heir. The execution of his brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd in 1283 on the orders of King Edward I of England effectively ended Welsh independence. The title of Prince of Wales was then used by the English monarchy as the heir to the English throne.[79]

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was the only ruler to unite all of Wales under his rule, described by one chronicler after his death as king of Wales. In 1055 Gruffydd ap Llywelyn killed his rival Gruffydd ap Rhydderch in battle and recaptured Deheubarth.[80] Originally king of Gwynedd, by 1057 he was ruler of Wales and had annexed parts of England around the border. He ruled Wales with no internal battles.[81][77] His territories were again divided into the traditional kingdoms.[77] John Davies states that Gruffydd was "the only Welsh king ever to rule over the entire territory of Wales... Thus, from about 1057 until his death in 1063, the whole of Wales recognised the kingship of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. For about seven brief years, Wales was one, under one ruler, a feat with neither precedent nor successor."[82] Owain Gwynedd (1100–1170) of the Aberffraw line was the first Welsh ruler to use the title princeps Wallensium (prince of the Welsh), a title of substance given his victory on the Berwyn range, according to Davies.[83] During this time, between 1053 and 1063, Wales lacked any internal strife and was at peace.[84]

High Middle Ages: 1066–1283

[edit]

Norman invasion

[edit]

Within four years of the Battle of Hastings (1066), England had been completely subjugated by the Normans.[82] William I of England established a series of lordships, allocated to his most powerful warriors, along the Welsh border, their boundaries fixed only to the east (where they met other feudal properties inside England).[85] Starting in the 1070s, these lords began conquering land in southern and eastern Wales, west of the River Wye. The frontier region, and any English-held lordships in Wales, became known as Marchia Wallie, the Welsh Marches, in which the Marcher lords were subject to neither English nor Welsh law.[86] The extent of the March varied as the fortunes of the Marcher lords and the Welsh princes ebbed and flowed.[87]

At the time of the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the dominant ruler in Wales was Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, who was king of Gwynedd and Powys. The initial Norman successes were in the south, where William Fitz Osbern overran Gwent before 1070. By 1074, the forces of the Earl of Shrewsbury were ravaging Deheubarth.[88]

The killing of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn in 1075 led to civil war and gave the Normans an opportunity to seize lands in North Wales. In 1081 Gruffudd ap Cynan, who had just won the throne of Gwynedd from Trahaearn ap Caradog at the Battle of Mynydd Carn was enticed to a meeting with the Earl of Chester and Earl of Shrewsbury and promptly seized and imprisoned, leading to the seizure of much of Gwynedd by the Normans.[89] In the south William the Conqueror advanced into Dyfed founding castles and mints at St David's and Cardiff.[90] Rhys ap Tewdwr of Deheubarth was killed in 1093 in Brycheiniog, and his kingdom was seized and divided between various Norman lordships.[91] The Norman conquest of Wales appeared virtually complete.

In 1094, however, there was a general Welsh revolt against Norman rule, and gradually territories were won back. Gruffudd ap Cynan was eventually able to build a strong kingdom in Gwynedd. His son, Owain Gwynedd, allied with Gruffydd ap Rhys of Deheubarth won a crushing victory over the Normans at the Battle of Crug Mawr in 1136 and annexed Ceredigion. Owain followed his father on the throne of Gwynedd the following year and ruled until his death in 1170.[92] He was able to profit from disunity in England, where King Stephen and Empress Matilda were engaged in a struggle for the throne, to extend the borders of Gwynedd further east than ever before.

Powys also had a strong ruler at this time in Madog ap Maredudd, but when his death in 1160 was quickly followed by the death of his heir, Llywelyn ap Madog, Powys was split into two parts and never subsequently reunited.[93] In the south, Gruffydd ap Rhys was killed in 1137, but his four sons, who all ruled Deheubarth in turn, were eventually able to win back most of their grandfather's kingdom from the Normans. The youngest of the four, Rhys ap Gruffydd (Lord Rhys) ruled from 1155 to 1197. In 1171 Rhys met King Henry II and came to an agreement with him whereby Rhys had to pay a tribute but was confirmed in all his conquests and was later named Justiciar of South Wales. Rhys held a festival of poetry and song at his court at Cardigan over Christmas 1176 which is generally regarded as the first recorded Eisteddfod. Owain Gwynedd's death led to the splitting of Gwynedd between his sons, while Rhys made Deheubarth dominant in Wales for a time.[94]

Dominance of Gwynedd and Edwardian conquest: 1216–1283

[edit]

Out of the power struggle in Gwynedd eventually arose one of the greatest of Welsh leaders, Owain Gwynedd's grandson, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, also known as Llywelyn Fawr (the Great). Llywelyn ab Iorwerth was sole ruler of Gwynedd by 1200[95] and by his death in 1240 was effectively ruler of much of Wales.[96] Llywelyn made his 'capital' and headquarters at Abergwyngregyn on the north coast, overlooking the Menai Strait. In 1200 he became King of Gwynedd and agreed to a treaty of peace with King John of England, marrying his illegitimate daughter Joan. In 1208, Llywelyn claimed the Kingdom of Powys after the arrest of Gwenwynwyn ap Owain by King John, who disapproved of his attacks on Marcher Lords of the South. Friendship broke down and John invaded parts of Gwynedd in 1211, taking Llywelyn's eldest son as hostage, and also forcing the surrender of territory in north-east Wales. Llywelyn's son, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, and other hostages were used as security by the king. However the Welsh and Scots joined English rebel Barons in forcing John to sign the Magna Carta of 1215. The document therefore holds specific Welsh provisions. These included the return of lands and liberties to Welshmen if those lands and liberties had been taken by English (and vice versa) without a law abiding judgement of their peers. Also the immediate return of Gruffydd and the other Welsh hostages.[97] Llywelyn went on to gain dominance over all Wales the following year.[98]

After the death of John in 1216, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth and the new King Henry III agreed to the treaty of Worcester in 1218, which confirmed Llywelyn's right to Wales until his death, recognising him as Prince of Wales.[98] Llywelyn ab Iorwerth received the fealty of other Welsh lords in 1216 at the council at Aberdyfi, becoming in effect the first prince of Wales.[99] His son Dafydd ap Llywelyn followed him as ruler of Gwynedd, but King Henry III of England would not allow him to inherit his father's position elsewhere in Wales.[100] War broke out in 1241 and then again in 1244, and the issue was still in the balance when Dafydd died suddenly at Abergwyngregyn, without leaving an heir in early 1246. Llywelyn the Great's other son, Gruffudd had been killed trying to escape from the Tower of London in 1244. Gruffudd had left four sons, and a period of internal conflict between three of these ended in the rise to power of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (also known as Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf; Llywelyn, Our Last Leader).[101][102][103]

Llywelyn ab Iorwerth's grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd secured the recognition of the title Prince of Wales from Henry III with the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267.[104] This treaty confirmed Llywelyn in control, directly or indirectly, over a large part of Wales.[105] A series of subsequent disputes, including the imprisonment of Llywelyn's wife Eleanor, culminated in a declaration of war and the first invasion by King Edward I of England in November 1276.[106][105] Realising his position was hopeless, Llywelyn II surrendered without battle. Edward negotiated a settlement, the Treaty of Aberconwy, which greatly restricted Llywelyn's authority and exacted Llywelyn's fealty to England in 1277.[106][107]

War broke out again when Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffudd attacked Hawarden Castle on Palm Sunday 1282. On 11 December 1282, Llywelyn was lured into a meeting in Cilmeri in Builth Wells castle with unknown Marchers, where he was killed and his army subsequently destroyed.[108] His brother Dafydd ap Gruffudd continued an increasingly forlorn resistance. He was captured in June 1283 and was hanged, drawn and quartered at Shrewsbury.[109] Following the deaths of Llywelyn and Dafydd, Edward ended Welsh independence, introducing the royal ordinance of the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284. The statute was a constitutional change annexing the Principality of Wales to the Realm of England, completing the Edwardian conquest.[110][111]

Late middle ages: 1283–1542

[edit]

The Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284 provided the constitutional basis for a post-conquest government of the Principality of North Wales from 1284 until 1535/36.[112] It defined Wales as "annexed and united" to the English Crown, separate from England but under the same monarch. The king ruled directly in two areas: the Statute divided the north and delegated administrative duties to the Justice of Chester and Justiciar of North Wales, and further south in western Wales the King's authority was delegated to the Justiciar of South Wales. The existing royal lordships of Montgomery and Builth Wells remained unchanged.[113] Wales became, effectively, part of England, even though its people spoke a different language and had a different culture. English kings appointed a Council of Wales, sometimes presided over by the heir to the throne. This Council normally sat in Ludlow, now in England but at that time still part of the disputed border area in the Welsh Marches. Welsh literature, particularly poetry, continued to flourish however, with the lesser nobility now taking over from the princes as the patrons of the poets. Dafydd ap Gwilym, who flourished in the middle of the 14th century, is considered by many to be the greatest of the Welsh poets.

After passing the Statute of Rhuddlan, which restricted Welsh law,[114] Edward constructed a series of castles to maintain his dominance: Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Harlech and Conwy.[115] This ring of impressive stone castles assisted the domination of Wales, and he crowned his conquest by giving the title Prince of Wales to his son and heir in 1301.[114] This son, the future Edward II, was born at Caernarfon in 1284.[116] When he became the first English prince of Wales in 1301, this provided an income from northwest Wales known as the Principality of Wales.[117]

There were a number of rebellions including ones led by Madog ap Llywelyn – who styled himself Prince of Wales in the Penmachno Document – in 1294–1295[118][119] and by Llywelyn Bren, Lord of Senghenydd, in 1316–1318. In the 1370s the last representative in the male line of the ruling house of Gwynedd, Owain Lawgoch, twice planned an invasion of Wales with French support. The English government responded to the threat by sending an agent to assassinate Owain in Poitou in 1378.[120]

The last uprising was led by Owain Glyndŵr, against Henry IV of England.[119] In 1400, Owain Glyndŵr, then a Welsh nobleman, revolted. Owain inflicted a number of defeats on the English forces and for a few years controlled most of Wales.[121] In 1404, Owain was crowned prince of Wales in the presence of emissaries from France, Spain (Castille) and Scotland.[119]Glyndŵr went on to hold parliamentary assemblies at several Welsh towns, including a Welsh parliament (Welsh: senedd) at Machynlleth.[122] Some of Glyndŵr's achievements included holding the first Welsh Parliament at Machynlleth and plans for two universities.[121] The rebellion was eventually defeated by 1412. Having failed Glyndŵr went into hiding and nothing was known of him after 1413.[123] Glyndŵr's rebellion caused a great upsurge in Welsh identity and he was widely supported by Welsh people throughout the country.[121]

As a response to Glyndŵr's rebellion, the English parliament passed the Penal Laws against the Welsh in 1402. These prohibited the Welsh from carrying arms, from holding office and from dwelling in fortified towns. These prohibitions also applied to Englishmen who married Welsh women. These laws remained in force after the rebellion, although in practice they were gradually relaxed.[124] The laws made the Welsh second-class citizens. With hopes of independence ended, there were no further wars or rebellions against English colonial rule and the laws remained on the statute books until 1624.[125]

In the Wars of the Roses, which began in 1455, both sides made considerable use of Welsh troops. The main figures in Wales were the two Earls of Pembroke, the Yorkist William Herbert and the Lancastrian Jasper Tudor. A Council of Wales and the Marches was created to rule Wales, by the Lancastrian Henry VI for his son Edward of Westminster in 1457. The Council was created again in 1471 by Edward IV for his son Edward V.[citation needed]

In 1485 Jasper's nephew, Henry Tudor, landed in Wales with a small force to launch his bid for the throne of England. Henry was of Welsh descent, counting princes such as Rhys ap Gruffydd among his ancestors, and his cause gained much support in Wales. Henry defeated King Richard III of England at the Battle of Bosworth Field with an army containing many Welsh soldiers and gained the throne as Henry VII of England. Henry VII again created a Council of Wales and the Marches for his son Prince Arthur.[126] Henry Tudor (born in Wales in 1457) seized the throne of England from Richard III of England in 1485, uniting England and Wales under one royal house.[127]

Welsh law was abolished and replaced by English law by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 during the reign of Henry VII's son, Henry VIII.[128] These laws integrated Wales with England in legal terms. As well as abolishing the Welsh legal system, the Welsh language could not be used for any official role. The laws also, for the first time, defined the Wales–England border and allowed members representing constituencies in Wales to be elected to the English Parliament.[129] They also abolished any legal distinction between the Welsh and the English, thereby effectively ending the Penal Code although this was not formally repealed.[130] In the legal jurisdiction of England and Wales, Wales became unified with the kingdom of England; the "Principality of Wales" began to refer to the whole country, though it remained a "principality" only in a ceremonial sense.[112][131] The Marcher lordships were abolished, and Wales began electing members of the Westminster parliament.[132]

Early modern period

[edit]

In 1536 Wales had around 278,000 inhabitants, which increased to around 360,000 by 1620. This was primarily due to rural settlement, where animal farming was central to the Welsh economy. Increase in trade and increased economic stability occurred due to the increased diversity of the Welsh economy and the passing of the Laws in Wales Acts.[133]

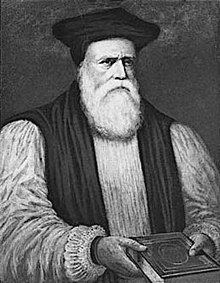

Following Henry VIII's break with Rome and the Pope, Wales for the most part followed England in accepting Anglicanism, although a number of Catholics were active in attempting to counteract this and produced some of the earliest books printed in Welsh. In 1588, William Morgan produced the first complete translation of the Welsh Bible.[134][d] Morgan's Bible is one of the most significant books in the Welsh language, and its publication greatly increased the stature and scope of the Welsh language and literature.[134]

Bishop Richard Davies and dissident Protestant cleric John Penry introduced Calvinist theology to Wales. Calvinism developed through the Puritan period, following the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II, and within Wales' Methodist movement. However, few copies of Calvin's works were available before the mid-19th century.[136] In 1567, Davies, William Salesbury, and Thomas Huet completed the first modern translation of the New Testament and the first translation of the Book of Common Prayer (Welsh: Y Llyfr Gweddi Gyffredin). In 1588, William Morgan completed a translation of the whole Bible. These translations were as important to the survival of the Welsh language and had the effect of conferring status on Welsh as a liturgical language and vehicle for worship. This had a significant role in its continued use as a means of everyday communication and as a literary language down to the present day despite the pressure of English. Wales was overwhelmingly Royalist in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the early 17th century, though there were some notable exceptions such as John Jones Maesygarnedd and the Puritan writer Morgan Llwyd.[137] Wales was an important source of men for the armies of King Charles I of England,[138] though no major battles took place in Wales. The Second English Civil War began when unpaid Parliamentarian troops in Pembrokeshire changed sides in early 1648.[139] Colonel Thomas Horton defeated the Royalist rebels at the battle of St. Fagans in May and the rebel leaders surrendered to Cromwell on 11 July after the protracted two-month siege of Pembroke.

Education in Wales was at a very low ebb in this period, with the only education available being in English while the majority of the population spoke only Welsh. In 1731, Griffith Jones started circulating schools in Carmarthenshire, held in one location for about three months before moving (or "circulating") to another location. The language of instruction in these schools was Welsh. By Griffith Jones' death, in 1761, it is estimated that up to 250,000 people had learnt to read in schools throughout Wales.[140]

The 18th century also saw the Welsh Methodist revival, led by Daniel Rowland, Howell Harris and William Williams Pantycelyn.[141]

Nonconformity was a significant influence in Wales from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries. The Welsh Methodist revival of the 18th century was one of the most significant religious and social movements in the history of Wales. The revival began within the Church of England in Wales and at the beginning remained as a group within it, but the Welsh revival differed from the Methodist revival in England in that its theology was Calvinist rather than Arminian. In the early 19th century the Welsh Methodists broke away from the Anglican church and established their own denomination, now the Presbyterian Church of Wales. This also led to the strengthening of other nonconformist denominations, and by the middle of the 19th century, Wales was largely Nonconformist in religion. This had considerable implications for the Welsh language as it was the main language of the nonconformist churches in Wales. The Sunday schools which became an important feature of Welsh life made a large part of the population literate in Welsh, which was important for the survival of the language as it was not taught in the schools. Welsh Methodists gradually built up their own networks, structures, and even meeting houses (or chapels), which led eventually to the secession of 1811 and the formal establishment of the Calvinistic Methodist Presbyterian Church of Wales in 1823.[142] The Welsh Methodist revival also had an influence on the older nonconformist churches, or dissenters the Baptists and the Congregationalists who in turn also experienced growth and renewal. As a result, by the middle of the nineteenth century, Wales was predominantly a nonconformist country.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution in Wales, there were small-scale industries scattered throughout Wales.[143] These ranged from those connected to agriculture, such as milling and the manufacture of woollen textiles, through to mining and quarrying.[143] Agriculture remained the dominant source of wealth.[143] The emerging industrial period saw the development of copper smelting in the Swansea area. With access to local coal deposits and a harbour that connected it with Cornwall's copper mines in the south and the large copper deposits at Parys Mountain on Anglesey, Swansea developed into the world's major centre for non-ferrous metal smelting in the 19th century.[143] The second metal industry to expand in Wales was iron smelting, and iron manufacturing became prevalent in both the north and the south of the country.[144] In the north, John Wilkinson's Ironworks at Bersham was a major centre, while in the south, at Merthyr Tydfil, the ironworks of Dowlais, Cyfarthfa, Plymouth and Penydarren became the most significant hub of iron manufacture in Wales.[144] By the 1820s, south Wales produced 40 per cent of all Britain's pig iron.[144]

In the late 18th century, slate quarrying began to expand rapidly, most notably in North Wales. The Penrhyn quarry, opened in 1770 by Richard Pennant, 1st Baron Penrhyn, was employing 15,000 men by the late 19th century,[145] and along with Dinorwic quarry, it dominated the Welsh slate trade. Although slate quarrying has been described as "the most Welsh of Welsh industries",[146] it is coal mining which became the industry synonymous with Wales and its people. Initially, coal seams were exploited to provide energy for local metal industries but, with the opening of canal systems and later the railways, Welsh coal mining saw an explosion in demand. As the South Wales Coalfield was exploited, Cardiff, Swansea, Penarth and Barry grew as world exporters of coal. By its height in 1913, Wales was producing almost 60 million tonnes of coal.[147]

The end of the 18th century saw the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, and the presence of iron ore, limestone and large coal deposits in south-east Wales meant that this area soon saw the establishment of ironworks and coal mines, notably the Cyfarthfa Ironworks and the Dowlais Ironworks at Merthyr Tydfil.[citation needed]

Modern history

[edit]1800–1914

[edit]The modern history of Wales starts in the 19th century when South Wales became heavily industrialised with ironworks; this, along with the spread of coal mining to the Cynon and Rhondda valleys from the 1840s, led to an increase in population.[148] The social effects of industrialisation resulted in armed uprisings against the mainly English owners.[149] Socialism developed in South Wales in the latter part of the century, accompanied by the increasing politicisation of religious Nonconformism. The first Labour MP, Keir Hardie, was elected as a junior member for the Welsh constituency of Merthyr Tydfil and Aberdare in 1900.[150]

The population of Wales doubled to over one million between 1801 and 1851 and doubled again, reaching 2,421,000 by 1911. Most of the increase came in the coal mining districts especially Glamorganshire.[151] Part of this increase can be attributed to the demographic transition seen in most industrialising countries during the Industrial Revolution, as death rates dropped and birth rates remained steady. However, there was also a large-scale migration of people into Wales during the industrial revolution. The English were the most numerous group, but there were also considerable numbers of Irish and smaller numbers of Italians, migrating to South Wales, as well as Russian and Polish Jews.[152]

The first decade of the 20th century was the period of the coal boom in South Wales when population growth exceeded 20 per cent.[153][page needed] Demographic changes affected the language frontier; the proportion of Welsh speakers in the Rhondda valley fell from 64 per cent in 1901 to 55 per cent ten years later, and similar trends were evident elsewhere in South Wales.[154][page needed]

The 1904–1905 Welsh Revival was the largest full-scale Christian revival of Wales of the 20th century. It is believed that at least 100,000 people became Christians during the 1904–1905 revival, but despite this it did not put a stop to the gradual decline of Christianity in Wales, only holding it back slightly.[155]

Historian Kenneth O. Morgan described Wales on the eve of the First World War as a "relatively placid, self-confident and successful nation". The output from the coalfields continued to increase, with the Rhondda Valley recording a peak of 9.6 million tons of coal extracted in 1913.[156] The First World War (1914–1918) saw a total of 272,924 Welshmen under arms, representing 21.5 per cent of the male population. Of these, roughly 35,000 were killed,[157] with particularly heavy losses of Welsh forces at Mametz Wood on the Somme and the Battle of Passchendaele.[158]

Kenneth O. Morgan argues that the 1850-1914 era:

was a story of growing political democracy with the hegemony of the Liberals in national and local government, of an increasingly thriving economy in the valleys of South Wales, the world's dominant coal-exporting area with massive ports at Cardiff and Barry, increasingly buoyant literature and a revival in the eisteddfod, and of much vitality in the nonconformist chapels especially after the short-lived impetus from the ‘great revival’, Y Diwygiad Mawr, of 1904–5. Overall, there was a pervasive sense of strong national identity, with a national museum, a national library and a national university as its vanguard.[159]

1914–1945

[edit]The world wars and interwar period were hard times for Wales, in terms of the faltering economy of antiwar losses. Men eagerly volunteered for war service.[160] The First World War and its aftermath had severe impact on Wales in terms of economic impact as well as war-time casualties. The result was significant social deprivation.[159]

The first quarter of the 20th century also saw a shift in the political landscape of Wales. Since 1865, the Liberal Party had held a parliamentary majority in Wales and, following the general election of 1906, only one non-Liberal Member of Parliament, Keir Hardie of Merthyr Tydfil, represented a Welsh constituency at Westminster. Yet by 1906, industrial dissension and political militancy had begun to undermine Liberal consensus in the southern coalfields.[161] In 1916, David Lloyd George became the first and only Welshman to become Prime Minister of Britain.[162] In December 1918, Lloyd George was re-elected as the head of a Conservative-dominated coalition government, and his poor handling of the 1919 coal miners' strike was a key factor in destroying support for the Liberal party in south Wales.[163] The industrial workers of Wales began shifting towards the Labour Party. When in 1908 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain became affiliated to the Labour Party, the four Labour candidates sponsored by miners were all elected as MPs. By 1922, half the Welsh seats at Westminster were held by Labour politicians—the start of a Labour dominance of Welsh politics that continued into the 21st century.[164] The Labour Party replaced the Liberals as the dominant party in Wales, particularly in the industrial valleys of South Wales. Plaid Cymru was formed in 1925, but initially, its growth was slow and it gained few votes at parliamentary elections.[165] Plaid Cymru sought sufficient autonomy or independence from the rest of the UK to ensure the survival of Welsh identity.[166]

After economic growth in the first two decades of the 20th century, Wales's staple industries endured a prolonged slump from the early 1920s to the late 1930s, leading to widespread unemployment and poverty.[167] For the first time in centuries, the population of Wales went into decline; unemployment reduced only with the production demands of the Second World War.[168] The war saw Welsh servicemen and women fight in all major theatres, with some 15,000 of them killed. Bombing raids brought high loss of life as the German Air Force targeted the docks at Swansea, Cardiff and Pembroke. After 1943, 10 per cent of Welsh conscripts aged 18 were sent to work in the coal mines, where there were labour shortages; they became known as Bevin Boys. Pacifist numbers during both World Wars were fairly low, especially in the Second World War, which was seen as a fight against fascism.[169]

Post war

[edit]

In the immediate period after the Second World War there was a strong revival in economic growth, accompanied by greater personal material well-being for the poorer elements of society as a result of the new systems of social welfare. Support for political nationalism strengthened with some success for Plaid Cymru and increasing pressure for Welsh devolution.[159] Personal incomes rose during the post war period; In 1962, for example, the average weekly wage of male manual workers stood at 315s 8d, compared with the UK average of 312s 10d. According to one study, “Only in the Midlands and the south of England were male manual wages higher than in Wales.”[170] Nevertheless, the coal industry steadily declined after 1945.[171] By the early 1990s, there was only one deep pit still working in Wales. There was a similar catastrophic decline in the steel industry (the steel crisis), and the Welsh economy, like that of other developed societies, tilted increasingly towards the expanding service sector.

The term "England and Wales" became common for describing the area to which English law applied, and in 1955 Cardiff was proclaimed as Wales's capital. Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (The Welsh Language Society) was formed in 1962, in response to fears that the language might die out if not required in government business.[172] Nationalist sentiment grew following the flooding of the Tryweryn valley in 1965 to create a reservoir to supply water to the English city of Liverpool. Although 35 of the 36 Welsh MPs voted against the bill (one abstained), Parliament passed the bill in 1957 and the village of Capel Celyn was submerged. This highlighted Welsh powerlessness in the face of the numerical superiority of English MPs in Parliament.[173] Separatist groupings, such as the Free Wales Army and Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru were formed, conducting campaigns from 1963.[174] Prior to the investiture of Charles III in 1969, these groups were responsible for a number of bomb attacks on infrastructure.[175] At a by-election in 1966, Gwynfor Evans won the parliamentary seat of Carmarthen, Plaid Cymru's first Parliamentary seat.[176]

By the end of the 1960s, the policy of bringing businesses into disadvantaged areas of Wales through financial incentives had proven very successful in diversifying the industrial economy.[177] This policy, begun in 1934, was enhanced by the construction of industrial estates and improvements in transport communications,[177] most notably the M4 motorway linking south Wales directly to London. It was believed that the foundations for stable economic growth had been firmly established in Wales during this period, but this was shown to be optimistic after the recession of the early 1980s saw the collapse of much of the manufacturing base that had been built over the preceding forty years.[178]

Devolution

[edit]

Meanwhile growing calls to recognise the Welsh language at an institutional level led to the passing of the Welsh Language Act 1967. The Welsh language was thus formally recognised as a legitimate language in legal and administrative contexts for the first time in English law.[179] The proportion of the Welsh population able to speak the Welsh language was declining, falling from just under 50% in 1901 to 43.5% in 1911 and reaching a low of 18.9% in 1981. It has risen slightly since.[180]

The Welsh Language Act 1967 repealed a section of the Wales and Berwick Act and thus "Wales" was no longer part of the legal definition of England. This essentially defined Wales as a separate entity legally (but within the UK), for the first time since before the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 which defined Wales as a part of the Kingdom of England. The Welsh Language Act 1967 also expanded areas where use of Welsh was permitted, including in some legal situations.[181][182]

In a referendum in 1979, Wales voted against devolution for Wales by an 80 per cent majority. In 1997, a second referendum on the same issue secured a very narrow majority (50.3 per cent).[183] The National Assembly for Wales (Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru) was set up in 1999 (under the Government of Wales Act 1998) with the power to determine how Wales' central government budget is spent and administered, although the UK Parliament reserved the right to set limits on its powers.[184]

The Government of Wales Act 2006 (c 32) of the UK Parliament reformed the National Assembly for Wales and allowed further powers to be granted to it more easily. The Act created a system of government with a separate executive drawn from and accountable to the legislature.[185] Following a successful referendum in 2011 on extending the law-making powers of the National Assembly, it was then able to make laws, known as Acts of the Assembly, on all matters in devolved subject areas, without needing the UK Parliament's agreement.[186]

After the Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act 2020, in May 2020 the National Assembly was renamed "Senedd Cymru" in Welsh and the "Welsh Parliament" in English, which was seen as a better reflection of the body's expanded legislative powers, commonly known as the "Senedd" in both English and Welsh.[187]

Welsh language

[edit]

The Welsh language (Welsh: Cymraeg) is an Indo-European language of the Celtic family;[188] the most closely related languages are Cornish and Breton. Most linguists believe that the Celtic languages arrived in Britain around 600 BC.[189] The Brythonic languages ceased to be spoken in England and were replaced by the English language, a Germanic language which arrived in Wales around the end of the eighth century due to the defeat of the Kingdom of Powys.[190]

The Bible translations into Welsh and the Protestant Reformation, which encouraged use of the vernacular in religious services, helped the language survive after Welsh elites abandoned it in favour of English in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[191]

Successive Welsh Language Acts, in 1942, 1967 and 1993, improved the legal status of Welsh.[192] The Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011 modernised the 1993 Welsh Language Act and gave Welsh an official status in Wales for the first time, a major landmark for the language. The Measure also created the post of Welsh Language Commissioner, replacing the Welsh Language Board.[193]

Starting in the 1960s, many road signs have been replaced by bilingual versions.[194] Various public and private sector bodies have adopted bilingualism to a varying degree and (since 2011) Welsh is the only official (de jure) language in any part of Great Britain.[195]

Historiography

[edit]Until recently, says Martin Johnes:

- the historiography of modern Wales was rather narrow. Its domain was the fortunes of the Liberals and Labour, the impact of trade unions and protest, and the cultural realms of nonconformity and the Welsh language. This was not surprising—all emergent fields start with the big topics and the big questions—but it did give much of Welsh academic history a rather particular flavour. It was institutional and male, and yet still concerned with fields of enquiry that lay outside the confines of the British establishment.[196]

See also

[edit]- History of the United Kingdom

- Welsh historical documents

- Archaeology of Wales

- List of Anglo-Welsh Wars

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gildas, writing c. 540, condemns the "tyrant of the Demetians".[33]

- ^ The earliest instance of Lloegyr occurs in the early 10th-century prophetic poem Armes Prydein. It seems comparatively late as a place name, the nominative plural Lloegrwys, "men of Lloegr", being earlier and more common. The English were sometimes referred to as an entity in early poetry (Saeson, as today) but just as often as Eingl (Angles), Iwys (Wessex-men), etc. Lloegr and Sacson became the norm later when England emerged as a kingdom. As for its origins, some scholars have suggested that it originally referred only to Mercia – at that time a powerful kingdom and for centuries the main foe of the Welsh. It was then applied to the new kingdom of England as a whole (see for instance Rachel Bromwich (ed.), Trioedd Ynys Prydein, University of Wales Press, 1987). "The lost land" and other fanciful meanings, such as Geoffrey of Monmouth's monarch Locrinus, have no etymological basis. (See also Discussion in Reference 40)

- ^ For a discussion of this, see [67]

- ^ "The year in which English independence was preserved by the defeat of the Armada was also the one in which the linguistic and cultural integrity of Wales was saved by Morgan's Bible."[135]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Davies 1994, p. 3.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 2.

- ^ Foster & Daniel 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Pettitt 2010, p. 207.

- ^ Richards & Trinkaus 2009.

- ^ Pollard 2001, pp. 13–25.

- ^ Davies 2008, pp. 647–648.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 2-3.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 7.

- ^ Lynch 2000, pp. 34–42, 58.

- ^ Whittle 1992.

- ^ Evans & Lewis 2003

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 17.

- ^ a b Davies 1994, pp. 4–6

- ^ Evans & Lewis 2003, p. 47

- ^ Pearson 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 9.

- ^ Lynch 1995, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c Davies 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Koch 2009

- ^ Cunliffe & Koch 2010, p. 384.

- ^ Cunliffe 2008, pp. 55–64.

- ^ Koch 2009b.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 19.

- ^ Lynch 1995, pp. 249–277.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Lynch 2000, p. 184.

- ^ Cunliffe 1978, p. 206.

- ^ a b Jones & Mattingly 1990, p. 151.

- ^ Webster 2019, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Jones & Mattingly 1990, pp. 154.

- ^ Giles 1841, pp. 27.

- ^ a b Jones & Mattingly 1990, pp. 179–196.

- ^ a b c d e Davies 2008, p. 915

- ^ a b Davies 2008, p. 531

- ^ Frere 1987, p. 354.

- ^ Giles 1841, p. 13.

- ^ a b Davies 2000, p. 78.

- ^ a b Koch 2006, pp. 1231–1233.

- ^ Phillimore 1887, pp. 83–92.

- ^ Phillimore 1888, pp. 148–183.

- ^ Vermaat n.d.

- ^ Bromwich 2006, pp. 441–444.

- ^ Harbus 2002, pp. 52–63.

- ^ Lynch 1995, p. 126.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Lloyd 1911a, pp. 143–159.

- ^ a b Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 345.

- ^ Ravilious 2006.

- ^ Lloyd 1911a, p. 131.

- ^ Maund 2006, p. 36.

- ^ a b Davies 1994, p. 56

- ^ a b Davies 1994, pp. 65–66

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 926

- ^ Hill & Worthington 2003.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 2

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 71

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 714.

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 186

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 388.

- ^ a b Lloyd 1911a.

- ^ Giles 1848, pp. 277–288, chpt 1,2.

- ^ Lloyd 1959.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 64.

- ^ Davies 1994, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Stephenson 1984, pp. 138–141.

- ^ Pierce 1959c.

- ^ Llwyd 1832, p. 62,63.

- ^ Maund 2006, pp. 50–54.

- ^ Lloyd 1911a, p. 337.

- ^ Lloyd 1911a, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Lloyd 1911a, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 911.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2001, p. 104.

- ^ Hill 2001, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Maund 2006, pp. 87–97.

- ^ Maund 1991, p. 64.

- ^ Turvey 2010, p. 11, 99-105.

- ^ Jones 1959.

- ^ Maund 1991, pp. 216-.

- ^ a b Davies 1994, p. 100

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 128

- ^ Maund 1991, p. 216.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 101.

- ^ Lieberman 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Lieberman 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Davies 1987, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Maund 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Remfry 2003, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Lloyd 1911b, p. 398.

- ^ Maund 2006, pp. 162–171.

- ^ Lloyd 1911b, pp. 508–509.

- ^ Lloyd 1911b, p. 536.

- ^ Moore 2005, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Moore 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Carpenter 2015.

- ^ a b Pierce 1959a.

- ^ Davies 1994, pp. 133–134

- ^ Lloyd 1911b, p. 693.

- ^ Turvey 2010, p. 96, 99-102.

- ^ Moore 2005.

- ^ Pierce 1959b.

- ^ Davies 1994, pp. 143–144

- ^ a b Powicke 1962, p. 409.

- ^ a b Davies 1994, pp. 151–152

- ^ Prestwich 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Davies 2000, p. 353.

- ^ Turvey 2010, p. 112.

- ^ Jones 1969.

- ^ Pilkington 2002, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Scott-Macnab 1999, p. 459.

- ^ Davies 2000, pp. 357, 364.

- ^ a b Davies 1987, p. 386.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 162

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 162

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 711

- ^ Moore 2005, p. 159.

- ^ a b c Davies 1994, p. 194

- ^ Moore 2005, pp. 164–166.

- ^ a b c Moore 2005, pp. 169–185.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 203

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 203

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 199.

- ^ Jenkins 2007, pp. 107–119.

- ^ Williams 1987, pp. 217–226.

- ^ Williams 1987, pp. 231ff.

- ^ Johnes 2019, p. 65–66.

- ^ Williams 1987, pp. 268–273.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 233.

- ^ Lieberman 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 232

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 258-259.

- ^ a b Davies 2008, p. 572.

- ^ Williams 1987, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Morgan 2009, pp. 22–36.

- ^ Jenkins 1987, p. 7.

- ^ Jenkins 1987, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 280.

- ^ Jenkins 1987, pp. 370–377.

- ^ Jenkins 1987, pp. 347–350.

- ^ Yalden 2004, pp. 293–324.

- ^ a b c d Davies 2008, p. 392

- ^ a b c Davies 2008, p. 393

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 818

- ^ Attributed to historian A. H. Dodd: Davies 2008, p. 819

- ^ Jones 2014, pp. 148, 149.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 183.

- ^ Davies 1994, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Morgan 1982, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Mitchell 1962, pp. 20, 22.

- ^ O'Leary 2002, p. 302.

- ^ Jenkins 1987.

- ^ Evans 1989.

- ^ Gitre 2004, pp. 792–827.

- ^ John 1980, p. 183.

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 284

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 285

- ^ a b c Morgan 2015, p. 95.

- ^ Phillips 1993, pp. 94–105.

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 461

- ^ UK Government n.d.

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 515

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 439

- ^ Morgan 1982, pp. 206–8, 272.

- ^ McAllister 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Morgan 1982, pp. 208–210.

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 918

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 807

- ^ Johnes 2013.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 533.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 649.

- ^ Davies 1994, p. 665.

- ^ Clews 1980, pp. 15, 21, 25–31

- ^ Clews 1980, pp. 22, 59, 60 & 216.

- ^ Evans 2000, p. 152

- ^ a b Davies 2008, p. 236

- ^ Davies 2008, p. 237

- ^ Baker 1985, p. 169.

- ^ Davies 1993, pp. 56, 67.

- ^ Senedd Cymru 2011.

- ^ Senedd Cymru 2020.

- ^ Wyn Jones 2012, p. loc:400.

- ^ Wyn Jones 2012.

- ^ Expert Panel on Assembly Electoral Reform 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Expert Panel on Assembly Electoral Reform 2017, p. 33-34.

- ^ Expert Panel on Assembly Electoral Reform 2017, p. 18, 33-34.

- ^ Davies 2014, pp. 1, 4.

- ^ Davies 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Davies 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Davies 2014, pp. 37, 39.

- ^ Davies 2014, p. 117, 120, 122–123.

- ^ Law Wales n.d.

- ^ Davies 2014, pp. 117, 121.

- ^ Davies 2014, p. 122–123.

- ^ Johnes 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, Colin (1985). Aspects of bilingualism in Wales. Clevedon, Avon, England : Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-0-905028-51-4. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Beddoe, Deirdre (2000). Out of the shadows : a history of women in twentieth-century Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0708315917.

- Bogdanor, Vernon (1995). The Monarchy and the Constitution. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-827769-9. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- Bromwich, Rachel, ed. (2006). Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Welsh Triads (3 ed.). University of Wales Press.

- Charles-Edwards, T M (2001). "Wales and Mercia, 613–918". In Brown, Michelle P; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Leicester University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7185-0231-7. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Carpenter, David (2015). "Magna Carta: Wales, Scotland and Ireland". Hansard.

- Clews, Roy (1980). To Dream of Freedom – The story of MAC and the Free Wales Army. Y Lolfa Cyf., Talybont. pp. 15, 21 & 26–31. ISBN 978-0-86243-586-8.

- Cunliffe, Barry W. (1978). Iron age communities in Britain : an account of England, Scotland, and Wales from the seventh century BC until the Roman conquest (2d ed.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-8725-X.

- Cunliffe, Barry W.; Koch, John T. (2010). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language, and Literature. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-475-3.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2008). A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 75, 2009, pp. 55–64. The Prehistoric Society. p. 61.

- Davies, Janet (1993). The Welsh language. Cardiff : University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1211-7. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- Davies, Janet (2014). The Welsh Language: A History (2 ed.). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 1, 4. ISBN 978-1-78316-019-8.

- Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- Davies, John (Ed) (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Davies, John (2009). The making of Wales (2nd ed.). Stroud [England]: History Press. ISBN 9780752452418. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Davies, R. R. (1987). Conquest, Coexistence and Change: Wales 1063–1415. History of Wales. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821732-3.

- Davies, R. R. (2000). The Age of Conquest. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198208785.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-820878-5.

- Davies, Russell (15 June 2015). People, Places and Passions: A Social History of Wales and the Welsh 18701948 Volume 1 (1st ed.). University of Wales Press.

- Evans, D. Gareth (1989). A history of Wales, 1815-1906. Cardiff : University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1027-4. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- Evans, Edith; Lewis, Richard (2003). "The Prehistoric Funerary and Ritual Monument Survey of Glamorgan and Gwent: Overviews. A Report for Cadw by Edith Evans BA PhD MIFA and Richard Lewis BA" (PDF). Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 64. Retrieved 16 December 2024. ;

- Evans, Gwynfor (2000). The Fight for Welsh Freedom. Y Lolfa Cyf., Talybont. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-86243-515-8.

- Foster, I. Ll; Daniel, Glyn (24 October 2014). Prehistoric and Early Wales. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-60487-7.

- Frere, Sheppard Sunderland (1987), Britannia: A History of Roman Britain (3rd, revised ed.), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-1215-1

- Geoffrey of Monmouth (1848). Giles, J.A. (ed.). . pp. 277–288 – via Wikisource.

- Gitre, Edward J. (December 2004). "The 1904–05 Welsh Revival: Modernization, Technologies, and Techniques of the Self". Church History. 73 (4): 792–827. doi:10.1017/S0009640700073054. ISSN 1755-2613. S2CID 162398324.

- Harbus, Antonina (2002). Helena of Britain in Medieval Legend. DS Brewer. pp. 52–63. ISBN 0-85991-625-1.

- Hill, David (2001). "Wales and Mercia, 613–918". In Brown, Michelle P; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Leicester University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7185-0231-7. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- Hill, David; Worthington, Margaret (2003). Offa's Dyke: history and guide. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1958-9.

- Jenkins, Geraint H. (1987). The foundations of modern Wales : Wales 1642-1780. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821734-X.

- Jenkins, Geraint (2007). A Concise History of Wales. pp. 107–119.

- Jenkins, Philip (2014). A history of modern Wales 1536-1990. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-87269-6.

- John, Arthur H. (1980). Glamorgan County History, Volume V, Industrial Glamorgan from 1700 to 1970. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 183.

- Johnes, Martin (November 2010). "For Class and Nation: Dominant Trends in the Historiography of Twentieth-Century Wales: Historiography of Twentieth-Century Wales". History Compass. 8 (11): 1257–1274. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2010.00737.x.

- Johnes, Martin (18 January 2013). Wales since 1939. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-84779-506-9.

- Johnes, Martin (September 2016). "People, Places and Passions—'Pain and Pleasure': A Social History of Wales and the Welsh, 1870-1945 . By Russell Davies". Twentieth Century British History. 27 (3): 492–494. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hww019.

- Johnes, Martin (25 August 2019). Wales: England's Colony?. Parthian Books. ISBN 978-1-912681-56-3.

- Jones, Barri; Mattingly, David (1990), An Atlas of Roman Britain, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers (published 2007), ISBN 978-1-84217-067-0

- Jones, Francis (1969). The Princes and Principality of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780900768200.

- Jones, J. Graham (2014). The history of Wales. Cardiff, Wales : University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78316-169-0.

- Jones, Thomas (1959). "GRUFFUDD ap LLYWELYN (died 1063), king of Gwynedd and Powys, and after 1055 king of all Wales". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopaedia, vol. IV. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- Koch, John (2009). "Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9 (2009)" (PDF). Palaeohispánica: Revista Sobre Lenguas y Culturas de la Hispania Antigua. Palaeohispanica: 339–351. ISSN 1578-5386. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- Koch, John T. (2009). "A Case for Tartessian as a Celtic Language" (PDF). Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica. 9.

- Laing, Lloyd; Laing, Jennifer (1990), "The non-Romanized zone of Britannia", Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 96–123, ISBN 0-312-04767-3

- Laing, Lloyd (1975), "Wales and the Isle of Man", The Archaeology of Late Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 400–1200 AD, Frome: Book Club Associates (published 1977), pp. 89–119

- "Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011". law.gov.wales. Law Wales. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Lieberman, Max (2010). The Medieval March of Wales: The Creation and Perception of a Frontier, 1066–1283. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-521-76978-5. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911a). A History of Wales: From the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Vol. I. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 19 January 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911b). A History of Wales: From the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- "CADWALADR (died 664), prince". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Llwyd, Angharad (1832). A history of Anglesey. pp. 62–63.

- Lynch, Frances M. B. (May 1995). Gwynedd: A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales. The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-117015-74-6.

- Lynch, Frances (2000). Prehistoric Wales. Stroud [England]: Sutton Pub. ISBN 075092165X.

- Maund, K. L. (1991), Ireland, Wales, and England in the Eleventh Century, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, ISBN 978-0-85115-533-3

- Maund, K. L. (2006). The Welsh Kings: Warriors, Warlords and Princes (3rd ed.). Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2973-6.

- McAllister, Laura (2001). Plaid Cymru : the emergence of a political party. Bridgend, Wales : Seren. ISBN 978-1-85411-310-8. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- McAllister, Laura; Campbell, Rosie; Childs, Sarah; Clements, Rob; Farrell, David; Renwick, Alan; Silk, Paul (2017). A parliament that works for Wales (PDF). Cardiff: National Assembly for Wales. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- Mitchell, Brian R. (1962). Abstract of British historical statistics. Cambridge [England]: University Press. ISBN 9780521057387.

- Moore, David (2005). The Welsh Wars of Independence: c.410–c.1415. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3321-9.

- Morgan, D Densil (2009). "Calvinism in Wales: c.1590–1909". Welsh Journal of Religious History. 4: 22–36.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1982). Rebirth of a Nation: Wales 1880–1980. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 208–210. ISBN 978-0-19-821760-2.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (2015). Kenneth O. Morgan : My Histories. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1783163236.

- O'Leary, Paul (2002). Immigration and integration : the Irish in Wales, 1798-1922. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0708317679.